A model for vortex reconnection

Ivan Delbende, in collaboration with Maurice Rossi (IJLRA).

Contents |

Objectives

Understanding topology changes in flows, and in particular vortex reconnection, is a crucial issue, e.g. to the singular behaviour of Navier--Stokes and Euler equations, to dissipation (Shelley 1993, Kida 1994, Moffatt 2002)... Reconnection processes are also observed at large scales in the aerodynamical context on wing-tip counter-rotating vortices. These structures are deformed through the Crow instability, and when the perturbation reaches sufficiently large amplitudes, they reconnect into a series of vortex rings, also potentially dangerous for following aircrafts. The goal of this work is to investigate this purely viscous process by DNS, to extract the main mechanisms and to build up the simplest possible model.

Description

A 3D direct simulation of Navier-Stokes equations has been carried out. The system

consists in two counter-rotating vortices along the  direction,

of radius

direction,

of radius  and circulations

and circulations  ,

the space between them (along

,

the space between them (along  ) being

) being  (typically 80% of the aircraft span).

(typically 80% of the aircraft span).

denotes the vertical direction. In a central region

hereafter called RCA (region of closest approach), a slight pinch resembling to

one wavelength of the Crow instability is put as initial condition.

denotes the vertical direction. In a central region

hereafter called RCA (region of closest approach), a slight pinch resembling to

one wavelength of the Crow instability is put as initial condition.

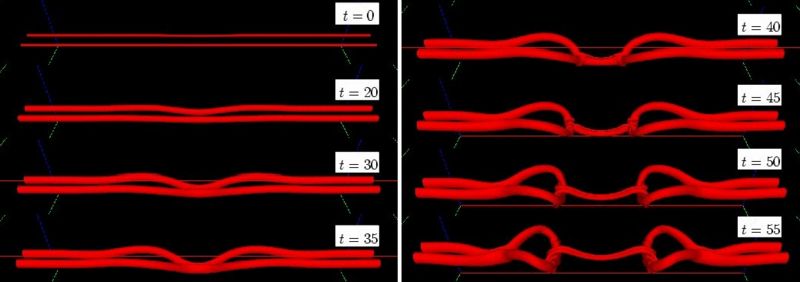

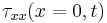

The time evolution presented on figure 1 shows several phases:

- For

the two vortices come close one to another in the RCA through Crow instability.

the two vortices come close one to another in the RCA through Crow instability.

- Around

the reconnection itself takes place rather rapidly: the vortices are laterally squashed in the RCA. In the vicinity of the RCA, vorticity reorients itself to form loops (clearly visible for

the reconnection itself takes place rather rapidly: the vortices are laterally squashed in the RCA. In the vicinity of the RCA, vorticity reorients itself to form loops (clearly visible for  ) interconnecting the two initially parallel vortices.

) interconnecting the two initially parallel vortices.

- In the RCA remains a small elongated dipole which branches off at the loops, is stretched by them and rolled up at its ends.

Results

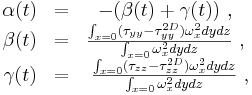

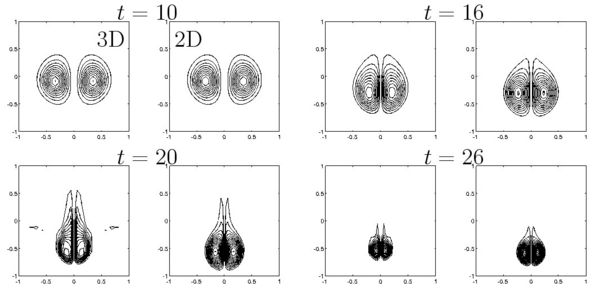

We could extract the mean main strain rates responsible for the above dynamics

in the plane of closest approach (PCA).

As we are concerned with 3D vortex curvature effects,

the total strain rates  and

and

in the PCA

have to be diminished by the (dominant) 2D mutual strain rate of

the two vortices

in the PCA

have to be diminished by the (dominant) 2D mutual strain rate of

the two vortices  and

and  , then averaged in the

PCA according to formula:

, then averaged in the

PCA according to formula:

where integrals are taken over the PCA (i.e.

where integrals are taken over the PCA (i.e.  ).

).

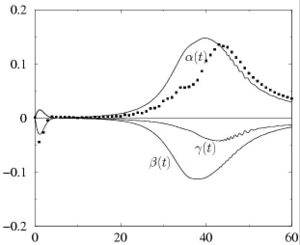

This gives the three main stain rates along  ,

,  and

and  presented as a function of time on figure 2. The dynamics in the RCA is thus dominated by lateral

compression (

presented as a function of time on figure 2. The dynamics in the RCA is thus dominated by lateral

compression ( ) and axial stretching (

) and axial stretching ( ).

).

In order to test the validity and pertinence of this approach, we have compared

- the axial vorticity in the PCA obtained by the 3D DNS

- the axial vorticity obtained through a 2D approach in which three-dimensionality is simply taken into account through a superimposed external strain (

).

).

The comparison is presented on figure 3 and shows good agreement.

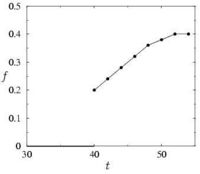

Closer inspection of the central dipole in the RCA reveals a phenomenon that had never been reported before and clearly visible on figure 4a: the two squashed elliptical vortices in the RCA eject a fraction of their vorticity to form a vertical dipolar vortex sheet above the RCA. The lateral compression due to 3D vortex curvature puts the vortices so close that their mutual 2D strain becomes larger than they can sustain: a fraction of the vorticity is then ripped off from the vortices (figure 4b), which then become totally passive under the influence of the newly formed reconnection loops.

Conclusions

With a 2D model, in which 3D vortex curvature effects are taken into account through a simple uniform unstationnary strain field, we were able to reproduce the dynamics at the reconnection point. Discepancies with Saffman's model (Saffman 1990) are found, namely the vorticity ejection whereby the dipole can give away more than 20% of its circulation. The work in progress aims at predicting quantitavely this value.

References

- Kida & Takaoka (1994) Vortex reconnection, Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech., Vol. 26, 169.

- Moffatt & Hunt (2002) A model of magnetic reconnection, in Tubes, Sheets and Singularities in Fluid Dynamics, Eds Bajer & Moffatt, 125, Kluwer Academic Publisher.

- Saffman (1990) A model of vortex reconnection, J. Fluid Mech., Vol. 212, 315.

- Shelley, Meiron & Orszag (1993) Dynamical aspects of vortex reconnection of perturbed anti-parallel vortex tubes, J. Fluid Mech., Vol. 246, 613.

,

,  . The selected vorticity level is half of the maximal vorticity far from the RCA.

. The selected vorticity level is half of the maximal vorticity far from the RCA.

,

,  ,

,  ) evaluated from the above DNS. Square symbols indicate the value of

) evaluated from the above DNS. Square symbols indicate the value of  estimated with passive particule trajectories.

estimated with passive particule trajectories.

for

for  .

.

. The central part of the dipole has ejected a vorticity sheet, visualised here thanks to a very low isosurface level.

. The central part of the dipole has ejected a vorticity sheet, visualised here thanks to a very low isosurface level.

of circulation contained by the sheet with respect to total circulation in the half-PCA.

of circulation contained by the sheet with respect to total circulation in the half-PCA.