Spoken versus written route directions

Marie-Paule Daniel & Edyta Przytula-Machrouh

Contents |

Introduction

The research presented here answers some questions about the effects of spoken versus written modality on text production. In our study, we examined the effects of the language modality on the production of a specific kind of spatial discourse : route directions. A major difference between spoken and written languages lies in differential working memory limitations. Chafe and Danielewicz (1987) found that oral language is less complex conceptually and grammatically but that sentences are shorter in speech due to short-term memory limitations. Working memory, which is responsible for the temporary storage and processing of information, plays a crucial role in complex activities such as language production and visuo-spatial thinking. Of course, spoken as well as written route directions imply working memory, especially its visuo-spatial component : in both cases, when describing a route, participants have first to activate and to maintain the internal representation of the route, then to plan the sequence of actions to be executed and lastly to find the best descriptors, the most appropriate words, in order to allow an addressee to understand and therefore complete the route. But whereas in the written situation, the describers can easily pause and re-read what they have just written, in the spoken one, they cannot similarly review what they have just said (Fayol, 1997). Consequently, the spoken situation, because of its specific characteristics, implies probably substantial increase of the cognitive load needed to achieve the route direction task. If so, the difference of modality should result in noticeable differences in the route descriptions generated. To what extent would the spoken route directions be different from the written ones? Answering this question was the aim of our study.

Participants

Participants were 97 undergraduates (45 female ; 52 male), attending courses at the Technical Institute of the Orsay campus (Institut Universitaire de Technologie, commonly designated IUT), aged 18-21. All were highly familiar with the environment traversed by the route to be described.

Materials

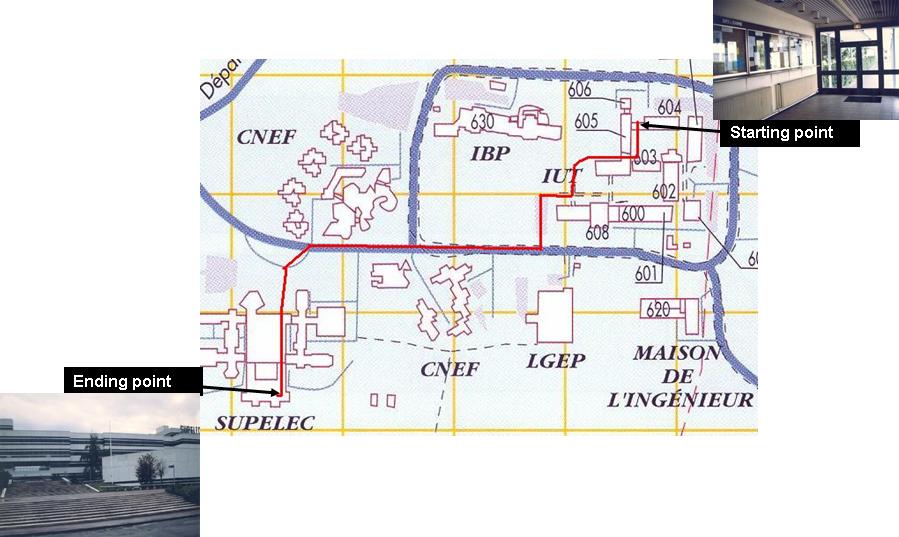

Study area : the environment used for this study was the Orsay university campus. The route selected for the experiment was 417 meters long. It started from the hall of the Technology Institute and ended at the cafeteria of an engineering school (Supelec). The route comprised four segments which were delimited by the main points of reorientation.

Procedure

In order to produce written texts, a describer is usually alone facing a blank sheet of paper, whereas, to produce spoken discourse she/he is facing an audience, or at least one person. In our experiment, all the participants were asked to describe a route to a supposed addressee who was not physically present in the room. In the written condition, the participants had to write down route directions on a sheet of paper, whereas in the spoken one, they had to deliver their directions on an answering machine. Therefore, in both cases, the describer was alone, without any interlocutor. The participants were given the following instructions: "Suppose that you have to describe to an addressee, a future student at the IUT, the route connecting the IUT to the Supelec cafeteria. Your description should start from the main hall of the IUT and include the entire route all the way to the entrance of the restaurant. This description is supposed to be published in the next brochure of the IUT (versus is supposed to be available on the answering machine of the IUT). Thus, it should be the most efficient as possible and arranged so that each new student does succeed to reach the cafeteria without mistaking and having to ask the way to anybody."

Half of the participants were invited to write down their descriptions on a sheet of paper. The other half were asked to describe the route verbally by phone. They were told that their message would help us to construct the final message which would be published in the next brochure of the IUT (alternatively would be left available on the answering machine of the IUT).

Results and Discussion

In order to assess the informational value of the descriptions, the content of each individual protocol was expressed in a proposition-like format following the method used by Denis (1997). Propositions were designed as minimal informational units combining a predicate and one or two arguments. For example, when a participant wrote: “Cross the courtyard (the one with a strange sculpture) to go towards the big lecture hall”, the protocol was recoded as a succession of the following statements: "cross the courtyard"; "there is a sculpture in the courtyard” "the sculpture is strange”; “go towards the big lecture hall”.

- Number of propositions.

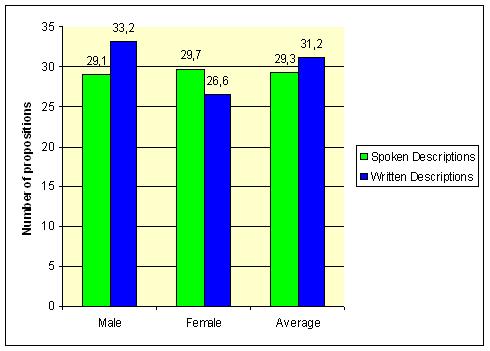

Inspection of the protocols revealed as frequently observed, the large variability of their length. Among the protocols collected in spoken condition, the number of propositions ranged from 14 to 62. In the Written Condition, it ranged from 15 to 62.

In both conditions (spoken versus written), the great majority of the descriptions (74%) ranged from 20 to 40 propositions.

Average number of propositions : in all, there is no global effect of the spoken versus written modality on the number of propositions contained in the descriptions : 29.3 for the spoken descriptions versus 31.2 for the written ones.

- Content of the descriptions.

The next step consisted in classifying the statements according to five different classes

- Class Actions (A): Prescription of action without reference to landmark.

- Class Actions with landmarks (AL) : Prescription of action with reference to landmark

- Class Landmarks (L): Introduction of landmark. A new landmark is mentioned without any associated reference to any action to be executed.

- Class Description of Landmark (DL): Description of landmark. In this case, the landmark is mentioned without either mention of localization or prescription of action, but its characteristic features are described

- Class Comments (C): This class contains comments which refer to the route without providing relevant information.

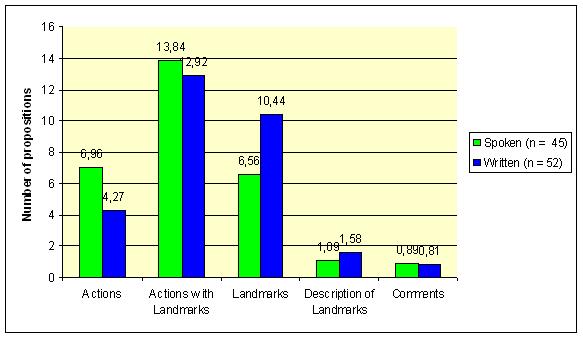

Whereas the modality doesn’t affect the average length of the descriptions, it does modify their content. The results show a clear effect of the modality (spoken versus written) with respect to two main points :

a) The spoken descriptions are more prescriptive than the written ones, in that they contain a higher number of propositions prescribing Actions. The average number of all prescribed actions (class A plus class AL, i.e. without and with associated landmark) is significantly higher in spoken descriptions than in written ones (20.80 [sd = 5.23] vs 17.19 [sd 3.77], F (1,95) = 15.12, p<.0002). The difference is also significant when considering the Actions class alone (6.96 versus 4.27), F (1,95) = 25.84, p<.000002.

b) The written directions are more descriptive than the spoken ones, in that they present a higher average number of propositions introducing Landmarks. Conversely, in all, the average number of all introduced landmarks (Class AL plus Class L) is lower in the spoken descriptions than in the written ones (20.40 [sd = 6.47] vs 23.36 [sd = 7.99], F (1,95) = 3.94, p<.05). The difference is also significant when considering the Landmarks class alone (6.56 versus 10.44, F (1,95) =13.42, p<.0004).

Moreover, the average number of landmarks mentioned in the written descriptions (17.06 [sd = 4,49]) is significantly higher than in the spoken ones (14.11 [sd = 3.93]), F(1,95) = 11.64, p<.0009.

Conclusion

Spoken versus written modality does affect the content of route descriptions. In our experiment, this effect cannot be ascribed to the interactional aspect of the oral situation, since half of the participants spoke to a “virtual interlocutor” whereas the other half wrote to a “virtual reader”. No real social interaction was present in any situation.

A main factor is likely to explain the observed differences between the two modes : the spoken situation requires the participants to produce more cognitive effort than the written one. Orally, they have simultaneously to keep active all the processes involved : keeping in mind altogether the shape of the route, the exact step where they are, the next step to be reached. In parallel, they also have to perform a comprehensive speech production. Therefore, in the spoken situation, the describers have to be highly concentrated, in order not to loose the thread of their thoughts. As the description goes along, mentally moving along the route to be described is probably helpful. In doing so, the describer is led to describe every necessary action, from a pedestrian point of view, as if she/he were really moving along the route. Consequently, the spoken mode leads to a very dynamic description, since the participant describes what she/he is doing. Conversely, in the written situation, the describer can take more distance with the route and thus describe the general surroundings of the route more precisely by introducing more landmarks. In this case, the participants are more likely to describe what they are viewing.

The results of our study show that, in any case, a written description is not simply a retranscription of a spoken one : the content is clearly different. Ideas appear to be actually different or at least coded differently in spoken and written forms.

References

Chafe, W., & Danielewicz, J. (1987). Properties of spoken and written language. In R. Horowitz & S. J. Samuels (Eds.), Comprehending oral and written language, ( pp. 83-113). San Diego: Academic Press.

Denis, M. (1997). The description of routes: A cognitive approach to the production of spatial discourse. Current Psychology of Cognition, 16, 409-458.

Fayol, M. (1997). Des idées au texte. Psychologie cognitive de la production verbale, orale et écrite, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France.